Mara | Philosophy | History

by Mara Carlson

CONTENTS

Tango Argentino: Prelude

Tango: The Rhythm of a New Reality

The Era of the Bordello

Bibliography

Tango dance on a patio, 1915

When I say ‘tango’ I mean the People…

those that from anonymity have created what is known as tango-dance,

the most wonderful of all dances.

—Rodolfo Dinzel

Prelude

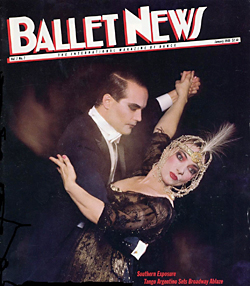

TANGO IS ONE OF THE MOST BEAUTIFUL and challenging dances that the world has known. More than a hundred years after its birth, the power of the original tango was demonstrated when the touring review Tango Argentino left its audiences gasping for more. Today the elegance, intimacy, and infectious beat of the Tango inspires aficionados from all parts of the globe to realize the intricacies of its form.

Tango is dark and elusive, a mystery, never fully realized, never fully known. It is a way to contemplate the strange beauty and imperfection within our collective condition as well as oneself. And it is a proving ground, where one may expand one’s awareness and authenticity, while endeavoring to comprehend its form.

Tango developed primarily in the region of the Rio de la Plata, the broad river plane shared by Argentina and Uruguay. In the coastal cities of Buenos Aires and Montevideo, it is not considered a true folk genre, but an urban style. Tango is a dance, it is a musical format with particular instruments and rhythmic structures, and it is poetry. It is also a complex social phenomenon that embraces a whole system of concepts, images, words, and practices. (Azzi, 1992, lecture) Originally the outcry of a socially and economically marginalized people, Tango is now a national symbol of Argentina. From its humble beginning in the riverfront slums it is now considered one of the great art traditions of the modern world.

In his novel On Heroes and Tombs Argentine author Ernesto Sábato remarks of his homeland: “Here we are neither Europe nor America, but a region of faults and fractures, an unstable, tragic, turbulent area where everything cracks apart and is ripped asunder.” (Sábato, 1981, p. 224) The Mexican author Carlos Fuentes confirms that Buenos Aires, “a city without a history, a repository, a transient city, must name itself in order to invent a past and imagine a future.” He adds that Tango then is a part of that naming. (Mendéz and Penón, 1988, p. 17)

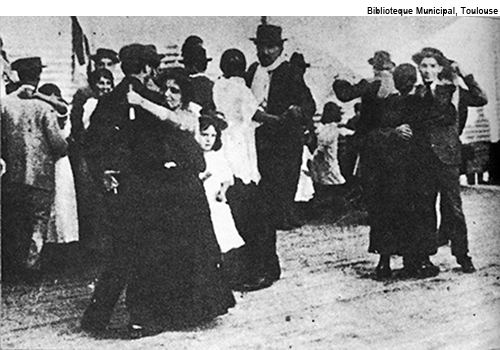

The Rose Pavilion, a popular dance venue in Buenos Aires, Carnival, 1905. Gradually the tango entered every strata of society, alternating with waltzes, mazurkas, polkas, and cake-walks.

By the end of the 19th century, Tango had become a way of life in the poorer neighborhoods–marking patterns of behavior, communications, and beliefs. Not unlike tap, break dancing, and hip-hop in our own urban ghettos, it afforded the less fortunate porteño a means whereby to prove his machismo, to enjoy a kind of celebrity, and perhaps to best the rich daddy’s boys.

In 1920, with the first radio broadcast programs, Tango’s popularity rose to astronomical heights throughout Argentina. By 1930, it had become an informal institution – giving voice and definition to the feelings, perceptions, memories, relations, art, and politics of millions of Argentines. (Azzi, 1992, lecture) In this way it came to inform, as well as reflect the Argentine vision of reality. Tango endures, not only through the self-acknowledged tanguero but also through those who may as yet be unaware that the history and heart of Tango shapes their responses to life and its experiences.

The essence of the tango is “a state of mind, a state of being: the sense of solitude and of longing. Tango is the tension on the brink of the void, the energy of desperation which, instead of succumbing to it, chooses to risk its life within music.”

—Tango Argentino, Program Notes

Arizona State University, 1987

Tango: The Rhythm of a New Reality

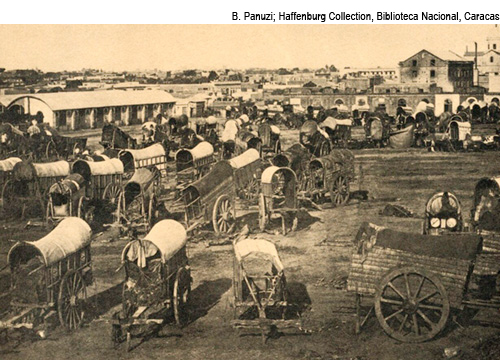

Wagon’s on Plaza, Buenos Aires, c. 1865: “La gran aldea” was marked by colonial architecture, narrow, muddy streets, and often insalubrious climate.

TANGO WAS BORN in the latter half of the 19th century in the arrabales (outskirts) of Buenos Aires, Argentina, and Montevideo, Uruguay. Like the social and musical trajectory of jazz, Tango developed amid the disenfranchised communities of African and Creole immigrants, far from the oligarchs and the bourgeoisie. It is considered a paradigm of Argentine popular culture. During the last hundred years it has so permeated all other art forms–theater, film making, literature, and even the plastic arts–that few reflections of Argentine culture are realized without some reference to tango. Tango has given a voice to the soul of the Argentine people; it is in their gestures, in their daily utterances, in the rhythm of their walk.

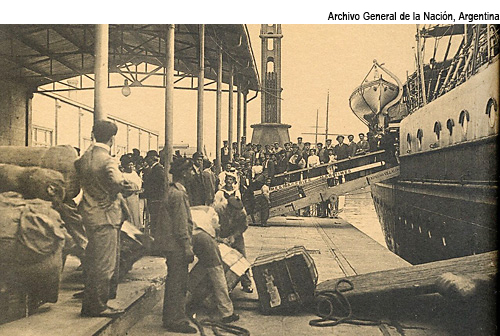

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Buenos Aires was little more than a backwater pueblo at the furthest corner of the Spanish Empire. However, post-industrialized countries of Europe began to eye Argentina in a new light, as they positioned themselves toward unbridled commercial expansion. To these powerful mercantile nations, Argentina, so rich in beef and wheat represented yet one more cache to claim. Resultant to political and economic agreements of the 1850’s, Britain constructed an immense railway network across Argentina, opening its vast territory and wealth.Rapidly expanding trade between Argentina and the Old World of raw materials for manufactured products led to the burgeoning wealth of landowners as well as the exploitation of the land’s resources. The Argentine government and members of the oligarchy advertised in Europe to meet the overwhelming demand for labor, offering accommodations and rations for a man’s first week in Argentina and even subsidized passage.

At the same time, Argentines, now fabulously wealthy from commerce and land speculation traveled abroad to acquire culture and merchandise unavailable at home, inspiring the phrase “rich as an Argentine.” The dream of many a nineteenth century Italian was hacer la America–to pick money off the streets of Buenos Aires. (Scobie, 2nd ed., 1971, p. 3) These immigrants, frequently lured by the promise of vast expanses of virgin country found the land already monopolized by huge estates. Many farmed as tenants, but far more sought employment and a future in the cities of the Rio de la Plata as stevedores, mechanics, bricklayers, clerks, servants, or factory laborers. (Ibid., p. 28)

Additionally, the transformation of Argentina’s rugged pastoral economy into the boom economy of a European outpost forced many rural Argentines to seek a livelihood in the port city of Buenos Aires. Between 1869 and 1914, both internal and external migrations caused the city’s population to mushroom from a modest 180,000 to more than 1.4 million. (Guy, 1991, p.38) And Buenos Aires began to emulate the ancient city of Babel, a vast labyrinth of immigrants, cultures, languages, and communities.

La Avenida de Mayo, Buenos Aires, 1894: After Buenos Aires became the national capital in 1880, construction took place at breathtaking speed, making it a showplace of the Western Hemisphere.

Despised by the upper and middle classes, impoverished immigrants withdrew to the suburban slums, mixing with inactive soldiers, displaced gauchos and other marginalized communities, populating the orilla at the city’s outskirts. Excluded from the rest of society, they established their own underground world with its own hierarchy and its own language. Lunfardo, a dialect made up of Spanish, Italian, pig-Latin, and slang, grew out of the need to communicate between diverse languages, as well as the criminal element’s desire to confound the authorities. Soon after, Lunfardo would be utilized by poet anarchists and adopted as the language of Tango.

Despised by the upper and middle classes, impoverished immigrants withdrew to the suburban slums, mixing with inactive soldiers, displaced gauchos and other marginalized communities, populating the orilla at the city’s outskirts. Excluded from the rest of society, they established their own underground world with its own hierarchy and its own language. Lunfardo, a dialect made up of Spanish, Italian, pig-Latin, and slang, grew out of the need to communicate between diverse languages, as well as the criminal element’s desire to confound the authorities. Soon after, Lunfardo would be utilized by poet anarchists and adopted as the language of Tango.

Black dance gatherings were originally termed “tambo” (drum). With the passing of time, however, the name metamorphosed into “tango”. Imitating the movement of black dances, compadritos (young street toughs) introduced cortes, quebradas, corridas, & incipient ochos into the traditional milonga, often termed “mother of the tango”.

The new citizen of Buenos Aires, having come from the pampa or from abroad, could not completely discard the musical forms of his homeland. Yet, a new music was needed to express his new urban reality. This music, the Tango, carries partial memories of the distinct musical forms of its gestation: the rural milonga of the gauchos, the Italian canzonetta, the Cuban habanera, the African candombe, and others. The lyrics of the Tango ballad may be traced to the payada, an improvised song dealing with contemporary events, often with overtones of social protest. (The Grove Dictionary for Music and Musicians, vol. 1, 1989, p.p. 570, 571) The candombe gave Tango not only its unique palpitation, but also choreographic elements. (Méndez and Penón, 1988, p. 25)

Even the bandoneon (a portable wind instrument similar to a concertina and diabolically difficult to master), which gave Tango its distinctive voice and resonant beauty, was an immigrant of Germany. Like its city, Tango resembles a broken mirror whose pieces reflect the fragments of a hundred cities, a hundred cultures. (Ibid., p. 17)

Sábato said that “the art of our time, that tense art that tears itself into bits and fragments, is invariably created out of our maladjustment, our anxiety, and our discontent – a sort of attempt at reconciliation with the universe on the part of that race of vulnerable, restless, covetous creatures that human beings are.” (Sábato, 1981, p. 443) Tango, created out of the disillusion and sorrow of society’s poor and outcast, shares in this dark and fatalistic vision.

I want to die with you

Without confession and without God

Crucified in my pain

As though pinned in rancor’s embrace.—Como Abrazao a Un Rancor, 1931

Lyrics by Antonio Miguel Podesta

Music by Rafael Rossi

Argentines believe, given the nature of humanity, that reality is ultimately tragic. But Sábato also said that “…man is made not only of desperation but of faith and hope, not only of death but of desire for life, not only of loneliness but of moments of communion and love.” (Ibid., p. 190.)

Tango emerged from the space between the immigrant’s dream and his harsh reality. It recalls the simplicity and dignity of an idealized past. It speaks of the childhood neighborhood, raw adolescence, and lost love, mourning amid the ash of remembered flames. In the words of Argentine author Javier Garcia Méndez and bandoneonist Arturo Penón, “It evokes a nostalgia that brings with it images of paradises, as apocryphal as they are lost, but it never fails to transport us…” (Méndez and Penón, 1988, p. 54)

Since 1870, life in the Rio de la Plata has undergone a host of radical modifications. Yet, despite the tremendous political and domestic strife woven throughout the Argentine experience, Tango continues to reflect the changing faces of reality, while rendering the soul of a past with longing and grace.

Born of the lowest elements of society, tango drew its parasitic strength from wicked impurities, yet it came to breathe new life into aristocratic circles with the exuberance of its passion. Its populist progenitors, not recognizing the beauty of this child, conceived of black days and sinful lust, had no idea that one day it would be reborn to scale the ramparts of ancient palaces that formerly glittered with noble European lineage.

—El tango: su evolucion y su historia.

Por Viejo Tanguero, La Nación, November 22, 1913

The Era of the Bordello

BY THE END OF THE NINETEENTH century, Buenos Aires was notorious as “the port of missing women” where “European virgins unwillingly sold their bodies and danced the tango.” (Guy, 1991, p. 5) At the time of tango’s genesis there were roughly seven men to every woman in this robust port city. Sexual commerce was rampant, and prostitution was legalized in 1885. Tango was defined and elaborated midst the sexual heat and danger of the brothels and music halls at the city’s outskirts. In its tragic lament, tango offers dignity and attitude to the desperate men and women whose lives gave it meaning.

Employment prospects for women were limited, and those that existed were poorly paid. Female prostitution became an integral part of the quasi-legal economy and culture of the poorer neighborhoods in Buenos Aires. (Ibid, p. 45) For the most part, both Argentine and European prostitutes descended from poverty-stricken families and worked out of desperation.

Employment prospects for women were limited, and those that existed were poorly paid. Female prostitution became an integral part of the quasi-legal economy and culture of the poorer neighborhoods in Buenos Aires. (Ibid, p. 45) For the most part, both Argentine and European prostitutes descended from poverty-stricken families and worked out of desperation.

For poor women, domestic service and sewing at miserable wages were among the few recourses to prostitution.

The only “respectable” positions to be had were as laundresses, seamstresses, and servants. While employment as actresses, café singers, and entertainers in music halls also existed, these earnings too were absurdly low. The impossibility of supporting oneself through any of these means then forced such women to supplement their income through prostitution. (Ibid, p. 149)

Sexual entertainment was as popular among elite males as among men of the lower classes. Before 1936, it was common for men of all classes to receive their sexual initiation in a bordello. A class hierarchy developed among the many brothels and nightspots. Some elegant establishments attracted an upper class clientele, some serviced only the poor, and others attracted both groups, who were likely to rub shoulders as they danced, conversed about politics, or slipped away to private rooms. (Ibid, p. 46)

In general, foreign prostitutes were considered more valuable than native, and French prostitutes, reflecting the Argentine predilection for French culture and merchandise, yielded the greatest return.

White slavery, venereal disease, disintegrating family values and gender relations were matters of great national concern. The prostitute became the proverbial scapegoat upon whom the upper and middle classes pinned the sins and ills of the nation. (Ibid, p. 44) Prostitutes were considered the carriers of disease and the origin of urban disorder–rather than its social and economic consequence. Prostitution was commonly attributed to the overwhelming female desire to buy clothing and jewels. Prostitutes were viewed as dangerous women who were linked with anarchists in nefarious plots to topple the Creole establishment culture. A plan to ‘beautify” Buenos Aires, as the newly established national capital, included restricting the necessary but unsavory business of prostitution to specified neighborhoods. Privileged Argentines then labeled these neighborhoods “sites of lower class damnation.”

White slavery, venereal disease, disintegrating family values and gender relations were matters of great national concern. The prostitute became the proverbial scapegoat upon whom the upper and middle classes pinned the sins and ills of the nation. (Ibid, p. 44) Prostitutes were considered the carriers of disease and the origin of urban disorder–rather than its social and economic consequence. Prostitution was commonly attributed to the overwhelming female desire to buy clothing and jewels. Prostitutes were viewed as dangerous women who were linked with anarchists in nefarious plots to topple the Creole establishment culture. A plan to ‘beautify” Buenos Aires, as the newly established national capital, included restricting the necessary but unsavory business of prostitution to specified neighborhoods. Privileged Argentines then labeled these neighborhoods “sites of lower class damnation.”

The period from 1870 to 1918 has been termed by many tango scholars and aficionados as the Bordello Era. During this period, tango music was often improvised and created primarily as the sub-stratum for the dance. Although relatively few lyrics were written, the earliest verses dealt with the wide range of social types encountered in porteño neighborhoods. Written in 1888, “Dame la lata” referred to the metal tokens given by customers to prostitutes and dance hall girls as proof of payment. Prostitutes, famous bordellos, madams, and female tango singers, as well as, mothers, laundresses, and percales, humbly dressed working-class women, became the poignant and sometimes obscene subjects of tangos. The early songs also referred to black Argentines, the renowned musicians and madams, a theme less commonly treated in the more polished tango-cancion of subsequent years. (Ibid, p. 144)

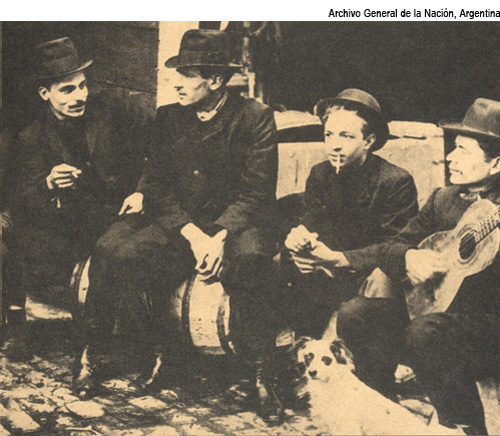

Real life compadritos: A group of coachmen, 1906. Working class young porteños who were among the early progenitors of the Tango.

The myth that Tango was “born in the brothels” of Buenos Aires and Montevideo has been transformed with time into a veritable axiom. (Méndez and Penón, 1988, p. 56) However, it seems more logical to assume that tango’s origins lay among the general populace of lower class neighborhoods, where amateur guitar, violin, flute, and clarinet players gathered in crowded tenement courtyards. On floors of packed earth or brick, Creoles and immigrants translated into dance the diverse musical structures of the pampa, Europe, and Africa. Among laborers and their families, the search for a style better suited to the new cadences of urban life eventually gave rise to the tango. (Ibid, p. 26)

Members of so-called high society considered the tango scandalous. During the brief period of his interest in popular culture, the great Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges wrote an article on the history of the tango. Referring to his personal recollections, to the essentially “lascivious” nature of the dance, and to the obviously obscene titles of some tangos, he proposed the theory of tango’s brothel origins. In reality though, this theory is no more than an exaggerated bourgeois perception of tango during its early years. (Ibid, p. 56)

Argentine author Javier Garcia Méndez and the bandoneonist Arturo Penón refute the Boghesian brothel theory as “the version of those who, at the turn of the century, shut the tango out of their lives…The patrician’s aversion to the tango was less a product of their prudery than it was a smokescreen, shielding their classist sensibilities from the trend’s real origins. To have allowed the tango into their exclusive gatherings would have been the equivalent of inviting those who created it into the sacrosanct dominant culture.” (Ibid)

Clearly, the bordellos, bars, cafes, and music halls were an integral part of the economic and social life of the poorer neighborhoods. And it does seem quite likely then, that the very same musicians who gathered in neighborhood courtyards could be found within the furtive realm of the local bordello plying their art and tasting the wares.

Circa 1910: Vicente Greco is credited with the “classical formation” of the tango ensemble, that is, La Orquesta Typica. His sextet of legendary fame was comprised of two bandoneons (a wind instrument almost synonomous with Tango), two violins, flute, and piano. Later Francisco Canaro, who had been one of the violinists in Greco’s sextet, replaced the flute with the bass, realizing a unique combination of musical voices that continues to withstand the test of time.

(to be continued)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Azzi, Maria Susana, (licenciada en ciencias antropologicas: Buenos Aires), lecture, University of Arizona, October, 1992.

Guy, Donna J., Sex and Danger in Buenos Aires, Lincoln and London: The University University of Nebraska Press, 1991.

Méndez, Javier G. and Penón, Arturo, The Bandoneon: A Tango History, [Le bandoneon depuis le tango, 1988] translated by Tim Barnard, Ontario: Nightwood Editions, 1988.

Sábato, Ernesto R., On Heroes and Tombs, [Sobre heroes y tumbas, 1961] translated by Helen R. Lane, Boston: David R. Godine, Inc., 1981.

Sábato, Ernesto R., The Outsider, [El tunnel, 1948] translated by Harriet de Onis, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1950.

Scobie, James R., Argentina: A City and a Nation, 2d ed., New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

“Tango Argentino Sets Broadway Ablaze”, Ballet News, vol.7, no.7, January 1986.

Copyright © 2009 by Mara B. Carlson. All rights reserved. No part of the website text may be reproduced without permission in writing of the author.